The maquis: neither fanatics nor bandits, fighters for freedom

"It causes a certain blush to read that they were bandits or bandits, because it was not so. The maquis was an organized movement that caused great concern in the Franco regime," he clarifies. Julian Chavezauthor of 'History of the maquis' (book attic, 2022). An essay in which this professor of Contemporary History at the University of Extremadura addresses one of the least known chapters of the early post-war years.

Subtitled 'The long road to freedom in Spain', Chaves's work is not limited to providing new information on this subject or bringing the already known information closer to the reader in a way that is as rigorous as it is entertaining, but rather dignifies the lives of those defeated who , contrary to what was affirmed by Franco's propaganda, they were not common criminals, nor adventurers or fanatics, but militants committed to freedom who They decided to fight the dictatorship through a strategy as Spanish as guerrilla warfare.

From escapees to maquis

On April 1, 1939, the Civil war. By then, almost all the Spanish provinces were under the command of a Francoist administration that, with more or less ease, had been subjugating those territories from the beginning. 1936 coup. This situation meant that, months before the armistice, many Republican fighters had to take refuge in the mountains to avoid being arrested or killed. They were "the runaways", soldiers who from then on developed a military strategy inherited from the 1808 guerrillas against Napoleon's army, and which had also been used by the Republican army during the war.

At the end of 1936, General Vicente Rojo, responsible for the defense of Madrid, launched the XIV Guerrilla Corps, a sort of irregular army whose objective was to infiltrate Franco's ranks to carry out actions of destabilization, sabotage and carry out espionage tasks.

With the Spanish War now over, the experience of the XIV Guerrilla Corps, added to that of the Republican soldiers who had fought in the french resistance against the Nazis, allowed to launch in Toulouse a school in which Republican militants were trained. Once formed, these cadres were transferred to Spanish territory where, in the fall of 1944, they staged a attempted invasion through the Aran Valley in which, in addition to infantry, battle tanks were used. "The invasion was rejected, which showed that there was no capacity to carry out operations of this type in the open field against the Francoist army. In return, they opted to train more guerrilla groups and try to organize these games politically," says Julián Chaves.

Thus, from the mid-1940s almost all the Spanish provinces had one or several guerrilla groups who carried out sabotage, expropriations and other actions aimed at destabilizing the Franco government. Despite its scarcity of resources, the successes of the maquis were relevant enough to draw the attention of the international media and worry the Francoist government, which deployed a strategy based on repression, terror and violence, in which There was a lack of perks in the form of promotions, decorations or economic remuneration for those members of the Civil Guard who detained or murdered members of the maquis.

The maquis was an isolated organization in the forest that, on many occasions, did not know what was happening just a hundred kilometers away"

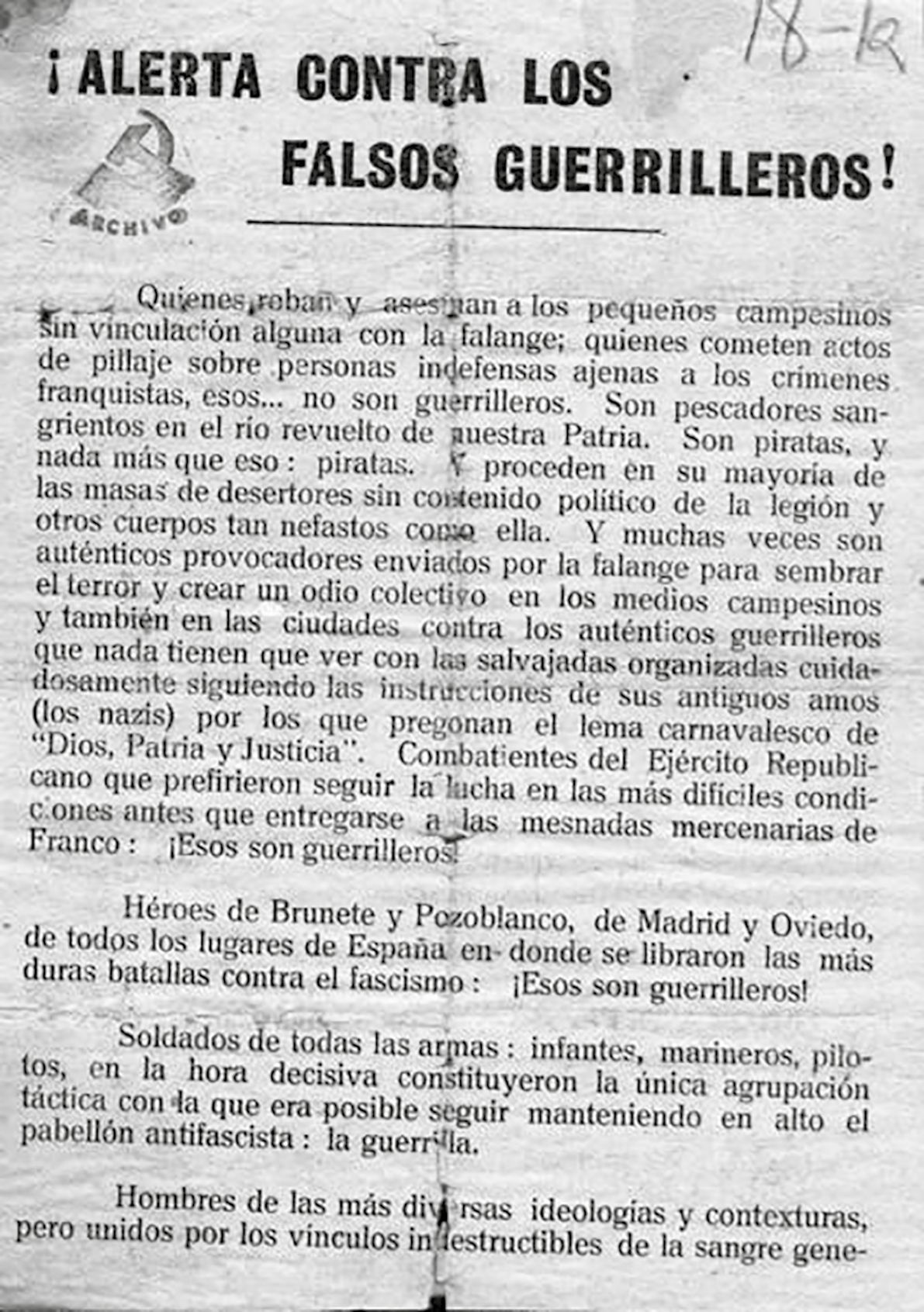

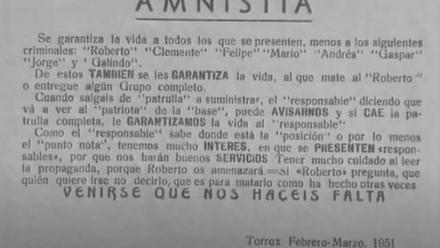

"The maquis was an isolated organization in the forest that, on many occasions, did not know what was happening just a hundred kilometers away. This situation meant that its success depended on the reciprocal trust between its members, the links and the support people responsible for buying supplies or medicines. Aware of this, the Francoist authorities focused their actions on forcing the accusation between the guerrillas", recalls Julián Chaves, who mentions among these methods the launching of leaflets in the mountains with messages to demoralize the members of the maquis, the creation of false guerrilla bands made up of civil guards to carry out false flag actions or "tortures to detainees to take them to an extreme situation in which they end up talking".

"If they have UN, we have two"

In 1946, the diplomatic efforts of the republican government in exile chaired by John Giral they got the United Nations Assembly approved an explicit condemnation of the Franco regime. Far from being a mere declaration of intent, that episode led to the departure of several international diplomatic representatives from Spanish territory and a commercial blockade of the country. However, the achievements made by Giral and the good prospects of his government, made up of anarchists, communists and socialists, ended up being diluted by the strange attitude of the latter.

"From the formation of the government in exile in August 1945, Indalecio Prieto was in favor of another policy. While Giral was a man of consensus who tried to activate diplomacy, Prieto was inclined towards an agreement with the monarchists and the celebration in Spain of a plebiscite to determine what your regimen should be in the future. That position led him to dialectical clashes with Giral, to the point that, when the UN declaration was achieved, Prieto disagreed with him and the socialist ministers resigned. This caused a crisis that, at the beginning of 1947, ended the Giral executive", explains Julián Chaves.

That same year, the Francoist government approved the Decree-Law on the repression of crimes of banditry and terrorism, which was decisive in the fight against the maquis. Among other provisions, this rule protected acts of violence by the Francoist authorities against the guerrillas and established the military criminal code to judge their actions, which could be punished even with the death penalty. This legal framework, added to the policy of extermination against members of the maquiscaused the Republican forces in exile to begin to question the suitability of the armed struggle.

The guerrilla struggle failed not only because of the actions of the army and the Civil Guard, but also because the international powers decided that there was no need to intervene"

The debate was resolved in 1948 with the decision of the Communist Party to put an end to the maquis. A few years later, the CNT he did the same with his urban guerrilla groups of Barcelona that, if they continued to be active for a few more years, it was due to the personal activity of militants such as Quico Sabate or Jose Luis Facerias. "The guerrilla struggle did not come to fruition, not only because of the forceful action of the army and the Civil Guard against the maquis, but also because the international powers decided that there was no need to intervene in Spain. United States and England they considered that Frank, which was called 'Sentinel of the West', was a greater guarantee when it came to preserving their interests in the country than a democratic system and they decided to support the dictator. From then on, the Communist Party ruled out fighting in the mountains and decided to transfer the struggle to the factory and the workers' centers."

a fair acknowledgment

On January 5, 1960, Francisco Quico Sabaté died as a result of injuries received a few days earlier during a confrontation with the police. The death of the anarchist militant put an end to the maquis and, except in isolated cases, also to the urban guerrillas, who would not make an appearance in Spanish society again until the appearance of the armed struggle movements of the late 1960s and early 1970s, some of which continued active once the dictatorship ended.

"In my opinion they are phenomena that are not related. The spiral of violence that characterized the last months of the Franco regime is not a continuity of what had been in the 40s, neither from the organizational point of view, nor in its purpose. While the maquis movement was a vindication of the Republic and of a democratic Spain capable of overthrowing the Franco regime, ETAthe FRAP or the GRAPO they obeyed a different code of conduct," clarifies Julián Cháves, who demands that the institutions value the work carried out by the maquis to restore freedom to the Spanish people.

"After years of books, articles, conferences and initiatives by associations related to the maquis, it seems that the Secretariat of Democratic Memory of the The current government is taking a qualitative leap in recognizing that the maquis was not banditry or banditrybut a pioneering movement of armed opposition against the Francoism, a regime whose origin, let us not forget, was in the arms. I understand that it will be a matter of time before that recognition arrives, and I humbly believe that this book will contribute to it," concludes Cháves.

Mothers and guerrillas

Republican women played a prominent role during the development of the Civil War. In addition to carrying out work in the rear, during the first months of the conflict they were militia women who came to fight on the front lines. After the war, many of them were a key piece for the maquis. "The role of women in the guerrilla is a fairly unknown subject. Most of the cases that I cite in the book began as links and collaborators. People who were paid by parties to get provisions, medicines, supplies... However, when their behavior was suspected, because in rural areas everyone knows each other, before returning home and running the risk of being arrested, many of these women they joined the maquis and were guerrillas," explains Julián Chaves, who highlights the special adversities that these fighters had to face in the mountains. "In the case of the women, the difficulties of the struggle in the mountains were added to others, such as, for example, that many of them became pregnant. After giving birth in secret, they had to leave their children in the sheepfold, in the farmhouse or in the outskirts of the town so that someone would take care of them. They were not abandoned, but ways of solving a specific situation, as shown by the fact that, later, some of them looked for those children and were reunited with Others, however, lost track of them and never knew their whereabouts."