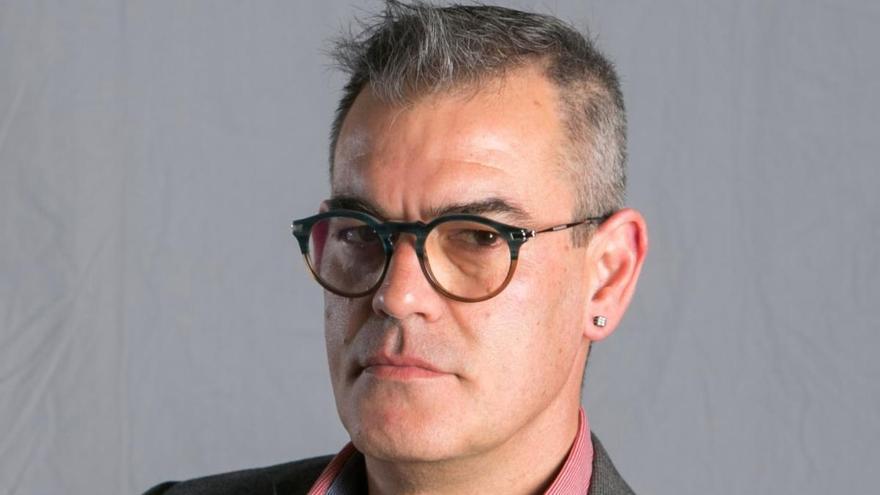

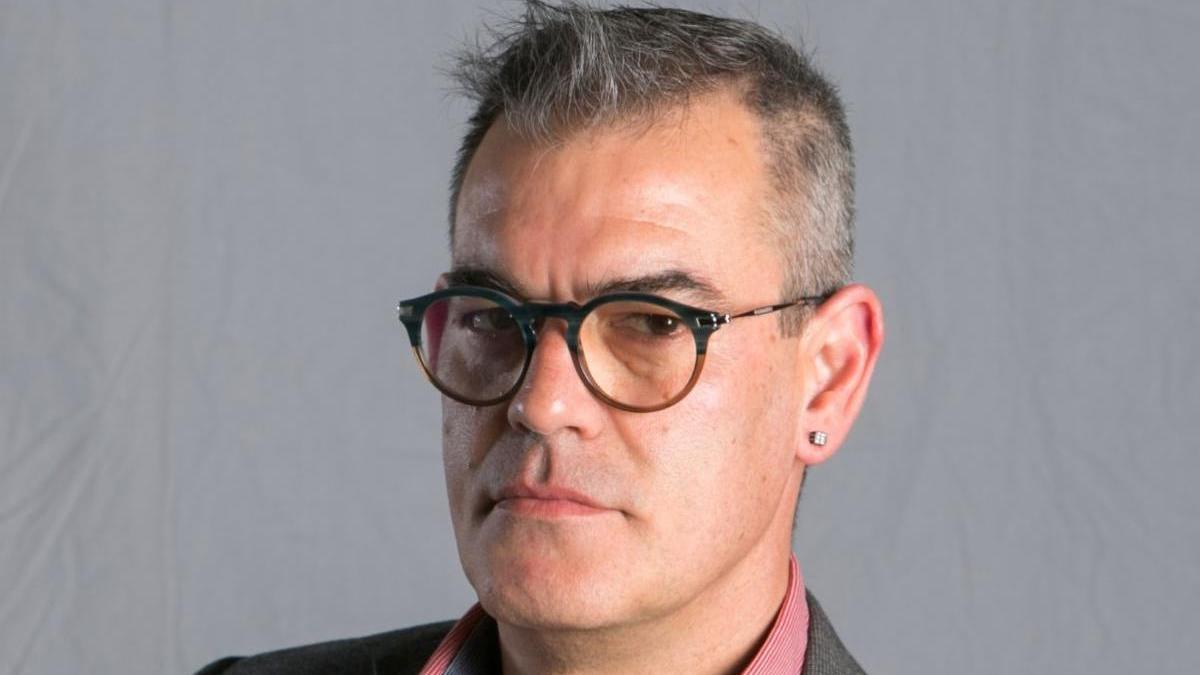

The exquisite corpse, by Jorge Fauró

At this point in history, demanding a 100% original text from an author is an entelechy. Finding an unpublished paragraph or unearthing a sentence surprising for its structure among the glossy pages of magazines, the ink stamped paper of newspapers, the lowercase sheets of books, the verses of a song or the terabytes of the Internet is a work of archaeologist. Nobody sings eureka in literature anymore. It is unlikely to discover in the relaxed strut of reading a composition that Quevedo or Cervantes had not written before; a concatenation of phrases that does not remind us of James Joyce or Marcel Proust; a style of writing that does not transfer us to Kerouac or Bukowski. As difficult as listening to a guitar riff not invented by Keith Richards.

Even novels that surprise in this infamous first quarter of a century (I recommend «2666», by Roberto Bolaño) invariably refer us to Joyce's Ulysses, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. It consoles me to think that in the days of the masters someone came to this same conclusion. Originality wiped out Tzara's Dada, the Exquisite Corpse, and Bréton's Surrealism, and yet none of it made much sense. The feeling of what is already known and that everything is already written. The Nobel laureates signed the act of surrender by granting the deserved recognition to Bob Dylan, a manual thief.

The Spanish alphabet straps the writing in 27 letters as the staff does in seven notes. From them, the rest make up variations on the same theme. The c with the ax forms the ch in the same way that between F and G there is an F sharp or G flat. The grace lies in knowing how to combine the elements in ways as finite or infinite as the instruction manual for a Rubik's cube. But everything obeys the same patterns and the same routines. Literature hides these days in a maximum of 280 characters, with sentences like whiplash, in millions of phrases that could adorn the galleys of an essay book or the great American novel. Scott Fitzgerald's apprentices and Stendhal's disciples sneak into a tangle of hatred and misspellings. This is also the new normal of art, in the same way that Photoshop has invaded photography or sprays, painting; the mobiles, the movies and television; the sand on the beach, the ephemeral sculpture; or the plastic modules, the architecture. The painting peaked with Mondrian and his childish vertical and horizontal lines of draftsman, but he was the first to do so and hence his greatness. Art ages because its artists age; rock and pop grow old because Jagger and McCartney grow old, as Bowie, Bolan, Jackson, and Lennon then died, and before Hendrix and Joplin. But rock had already died with Elvis, from which everything was combinations on seven musical notes. Football aged with the withdrawal of Pelé, but has died with Maradona. From now on everything will be variations on the same play because Villa Fiorito kids will want to score goals with their hand and emulate the idol's dribbling, as will thousands of children on artificial grass pitches and in so many mud and dust-spattered openings in Europe, Africa and Latin America.

The same is true for art, for literature, for painting. New artists will be born who will base their creations on the previous movement and a new genius will emerge that references them all. In art everything is already invented. In football too. We only have technology and science to continue with our evolutionary phase towards other ages of men and women. The rest - it has already been said - is literature.